Is Parmesan the same as Parmigiano Reggiano?

I want to answer a question I’ve been wondering every time I walk up to the cheese counter at the store…is Parmigiano Reggiano actually worth it?

Because when compared to other parmesan products you can find, it’s always the most expensive.

I purchased 5 different parmesan products at varying price points and researched how these are made (and regulated before). Then I tasted each product in 3 different experiments so we can get to the bottom of this.

I have heard countless confusing claims over the years. For example:

“Fake parmesan will clump up and be grainy so you should always buy real stuff”

I also have questions like:

What do people even mean by ‘real’ or ‘fake’ parmesan?

Is the green bottle of pre-grated stuff even made out of cheese?

Are parmesan and Parmigiano Reggiano the same thing?

How do I know if I’m getting Parmigiano Reggiano from Italy?

And maybe the most important question:

Can you actually even taste the difference between US-made and Italian-made Parmesan?

In this article, my goal with this is to arm you with all the knowledge and terms so you know exactly what every parmesan product is offering in order to make a nuanced answer based on your unique situation as a home cook.

For example:

Does it make more sense to blow the budget on DOP Parmigiano Reggiano and get cheap tomatoes and pasta or should I get the nice tomatoes and pasta and settle for one of the cheaper US-made parmesan options?

Let’s start with how parmesan-style cheese is made in the first place because surprisingly, all of our test products start with the same 3 ingredients: milk, salt, & cheese cultures.

Section 1: How is Parmesan Made?

According to the European Union D.O.P, “Parmigiano Reggiano is a hard cheese made from raw cows milk”

The only ingredients allowed are:

Milk

Salt

Rennet

(although the milk is a combination of skimmed, whole, and separated whey from the previous day’s process)

The process of turning the milk into cheese goes like this:

A combination of skimmed milk and whole milk is mixed with a whey starter, a natural culture of lactic acid and bacteria. The milk is heated to 36 C and mixed with calf rennet, and natural coagulant, which start the curdling the milk.

The curd is cut and separated from the whey, then the whole mixture is cooked at a higher temp (55C), which causes the curds to expel out any remaining whey liquid and sink to the bottom as cooked cheese curds. Then the whey is strained off.

The cheese curds are pressed into a mold (4 days in the mold), and salted in a brine to draw out moisture and form a rind (19 days), then aged dry for at least 12 months.

Here’s a chart from “On Food & Cooking” by Harold McGee that shows how the parmesan process compares to other cheeses.

History of Parmigiano Reggiano

According to the Italian Cheese Consortiums website

Parmigiano Reggiano's origins started 1000 years ago in the middle ages, with the same three ingredients they use today (milk, salt, and rennet)

The cheese was primarily made in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy and got its name from two cities in this region: ‘Parma’ & ‘Reggio Emilia’

As far back as 1612, 160 years before the US was even the US, the cheese already was starting to be regulated with a deed signed by the Duke of Parma that defined the places where cheese called “from Parma” could actually come from.

As the Parmigiano Reggiano move into modern times, this designation was expanded. In 1934 the dairies in this region of Italy agreed they needed a mark of origin for their cheese.

And now today, if you are part of the European Union and want a cheese to be considered and stamped as legit Parmigiano Reggiano there is an extremely specific location and process in which it must be made.

It’s all summed up in a single document from the official European Union: PDO-IT-02202, titled ‘Parmigiano Reggiano’.

Download-the-Single-document-of-the-PDO-Parmigiano-Reggiano (1).pdf

This thing is an interesting read-through, as there are some very specific measures, for example, you have the obvious ones like the three ingredients that must be used, the defined location where the cows come from, the size of the wheel, and how long it must be aged. But it goes into even deeper and more granular requirements like:

The cyclopropane fatty acid ratio has to be less than 22 mg per 100 grams of fat

and 75% of the food that that cow itself eats actually has to be produced within the geographic area, so those cows better not be munching on any grass grown in France.

What’s the Difference Between Parmigiano Reggiano & Parmesan?

Okay, so these requirements outline exactly what Parmigiano Reggiano is but what does it mean if cheese is labeled parmesan then?

And this is where the “it depends” comes in.

The word “parmesan” is the English translation of “Parmigiano Reggiano”,

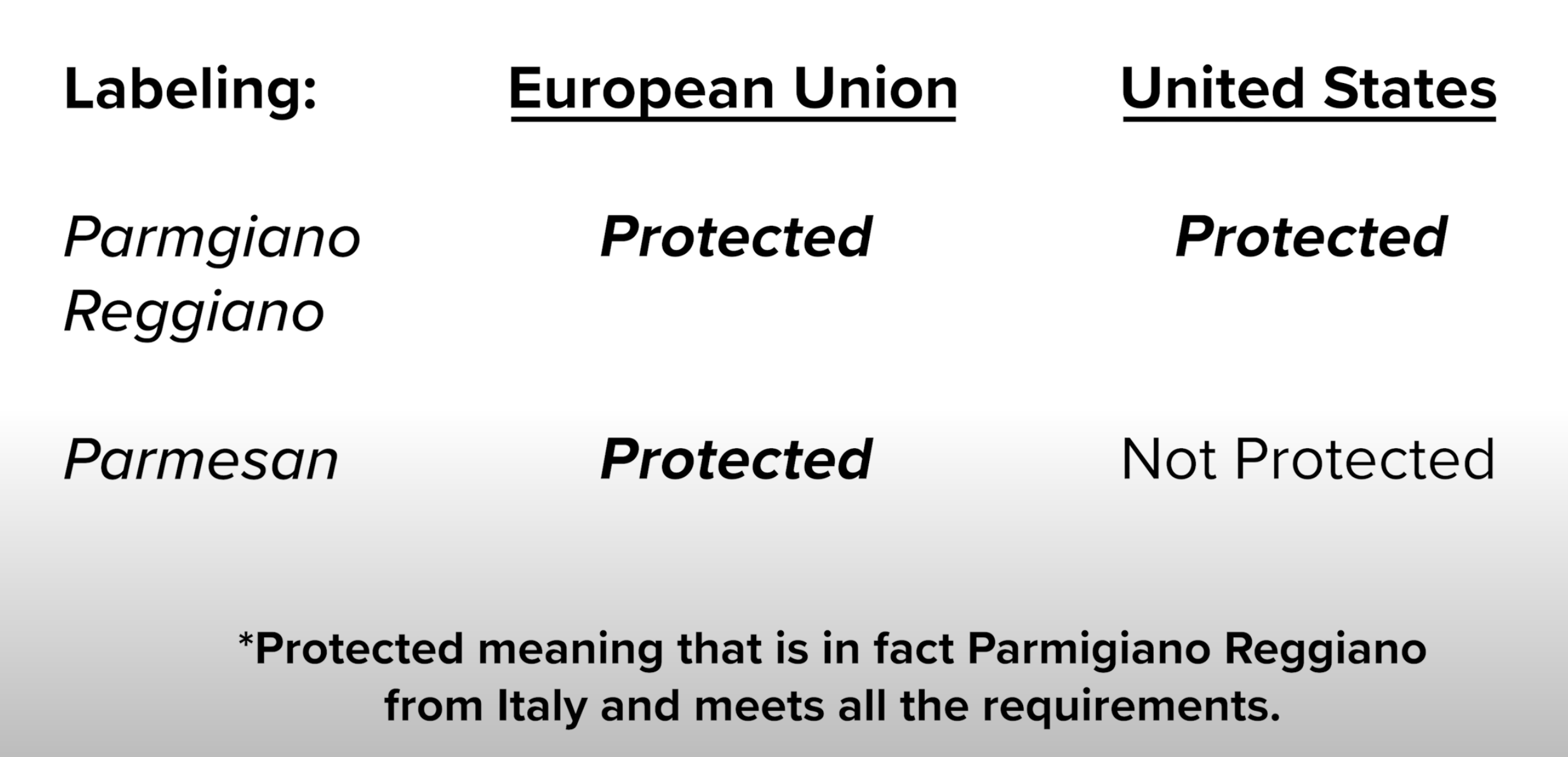

If you’re in the European Union, here’s what you can count on: If you see a cheese labeled parmesan at a shop in say France or Germany, it is Parmigiano Reggiano, meaning it was made in Italy and upholds all the standards.

This is codified into EU law.

On 26 February 2008, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that, in the EU territory, the term "Parmesan" is an evocation of the Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and, for that reason, it shall be used only for the true Parmigiano Reggiano, made in compliance with its Production Specifications.

Where it is noted that the term “Parmesan” is an evocation (or extension) of Parmigiano Reggiano PDO

And this is where it gets interesting.

What if some cheesemaker in the US just copied all the same steps down to the tee?

So say someone made a wheel of cheese in the exact same way that Parmigiano Reggiano is made down to the absolute tee. What if it looked exactly the same, it was aged the appropriate amount of time and met all the technical levels of size, fat level, and taste, but it was made with cows milk from Germany?

And what if even the most discerning Italian couldn’t tell the difference in a blind taste test?

Doesn’t matter. That cheese still cannot legally be labeled as parmesan in the European Union.

Apparently, the EU sued Berlin back in 2004, for not upholding the name ‘Parmesan.’

So in the EU “parmesan” and “Parmigiano Reggiano” are the same.

But this is not the case in the US, unfortunately.

Parmesan vs. Parmigiano Reggiano in the US

In the US, the term “Parmigiano Reggiano” is still protected but the word “parmesan” is not.

It’s the exact same as how in the US we use the word Champagne to generically refer to sparkling wines, but in the EU, if a bottle is labeled Champagne it is the specific sparkling wine from the Champagne in France.

If you see something labeled “parmesan” at a US grocery store, it is a generic term used to refer to a cheese made in a style similar to Parmigiano Reggiano, you have to take a look at the label, understand how cheese is made, and maybe do a taste test to see if it’s worth it.

Now the EU would consider the 4 US-made products on the right fake or counterfeit parmesan, but this is perfectly legal labeling in the US. The FDA does have some basic documentation about how something labeled parmesan is supposed to be made as well, but there are way fewer restrictions around the process.

Now there are definitely pros and cons to the EU vs. US approach in how the cheese is regulated. While interesting, that’s a whole separate conversation.

What most home cooks in the US are wondering is: how do I find the real stuff at an American grocery store?

Finding Parmigiano Reggiano in US Stores

Since Parmigiano Reggiano is a protected name, in the US, it’s really easy to figure out, especially compared to the canned tomato market.

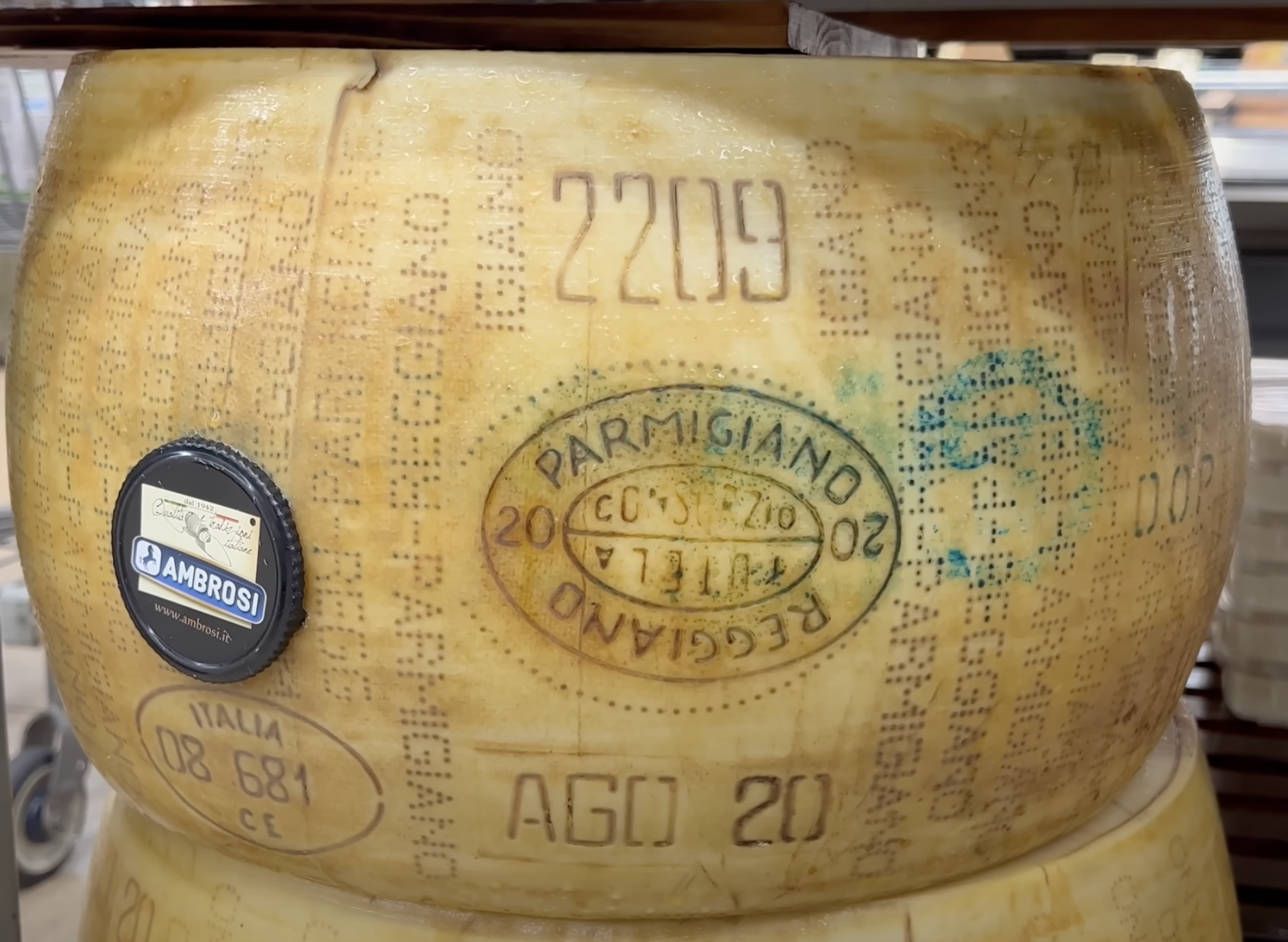

First, take a look at the name. If it's labeled ‘Parmigiano Reggiano’ it is indeed the legit stuff.

If you see it’s labeled ‘Parmesan’ assume that it is made with milk or processed in the US.

So the name on the label should be enough, but additionally, you can check for the DOP stamp on the cheese packaging.

And further, if you buy a hunk from the rind and the last check you can do is check the needle stamp that will also say Parmigiano Reggiano.

But again since the words “Parmigiano Reggiano” are protected everywhere that alone should be enough for you to shop with confidence.

Section 2: Taste Testing Takeaways

Up to now, we’ve touched on the history, regulation, and common labeling semantics, but none of that information really helps us answer the original question “Is Parmigiano Reggiano worth it?

So I did a few taste tests.

There were 3 important areas to keep in mind during these tests.

Flavor: Does Parmigiano Reggiano have a significantly better flavor compared to the parmesan alternatives?

Food Properties: Does it have advantageous food properties such as:

Higher fat content?

Does it melt better?

Do any additives make a difference?

Lifestyle: How is it going to be used?

For example, we may use it in a shaved garnish on a salad, sprinkle over some pizza, or use it in some pasta sauce like an alfredo or carbonara, so the recommendation may change.

And for me, I chose 3 tests that you can easily replicate at home to start to evaluate

Raw taste test

Traditional Alfredo Sauce Taste Test

Pizza Garnish Taste Test

Here are the candidates I tested:

First, we have the classic pre-grated green bottle, second, a 16-month pre-grated, a whole block 12-month aged US domestic, a whole 20th-month aged US domestic, and a whole block 24-month DOP certified Parmigiano Reggiano from Italy.

So let’s hop into the raw taste test first, for this initial one, I grated the blocks of parmesan, blindfolded myself, and tasted a small spoonful of each one.

Taste Test #1 - Raw

There were two clear takeaways from this test.

First in terms of flavor:

Yes, the DOP-aged Parmigiano Reggiano did taste the best, but the 20-month US was also quite good too. The 12-month was noticeably milder.

Secondly, in terms of food properties:

All three of the whole blocks that were grated melted in my mouth while both the pre-grated options lingered on my tongue. The pre-grated green bottle was so dry, almost like a powder.

So after this test, you may be wondering why does the aged parmesan taste noticeably better than the younger ones, and why didn’t the pre-grated options melt in my mouth as well?

Raw Flavor Difference Factors from Italian vs. American Production

And to answer that, let’s get into the 4 major variables that make Parmigiano Reggiano different from US-made parmesan:

Aging Time

Pasteurized Milk vs. Raw Milk

Additives/Preservatives vs. Zero Additives

Geography, Cow’s Diet, & Cheesemaking Process

And when broken into US vs EU parmesan here is a table that begins to show the differences in the actual makeup of these cheeses:

I want to start with aging which is probably the most important decision you have to make as a home cook at the cheese counter, because in general when it comes to cheese, aging has a massive impact on the final product in terms of both taste and texture.

1. Aging Time

Official Parmigiano Reggiano must be aged for at least 12 months, and keep in mind that’s after the almost month-long brining process that gives the parmesan wheels that beautiful, hard rind, which you just don’t find on domestic versions.

While the minimum aging time is 12 months, it can be aged 24, 36, 40, and even 100 months! There’s actually no maximum maturation time, according to the official website.

If you are in Italy you’ll be able to find a full range of aged parmesan cheeses really easily, but in a US grocery store that’s not the case. The most common imported Parmigiano is aged 24 months, which there is likely some cost-benefit analysis done by grocery stores.

Now it’s a completely different story when it comes to aging times for parmesan made in the US.

Based on this title 21 from the FDA last updated in 1993, the minimum aging time for parmesan is 10 months:

CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21

Most of the US-made parmesans I found at the store were 10 or 12 months, but you can find US-made brands that do age their cheeses for 20 or 24 months, but anecdotally they are kind of hard to find, it took me like 5 grocery store visits.

https://www.belgioioso.com/products/extra-aged-american-grana/

In general, if you have tried any aged cheeses you know it is going to be drastically different than its minimum aged counterpart (for example, a young cheddar vs. an aged one, or a 10-month parmesan vs. a 24-month parmesan).

And at a high level, 2 things happen when cheese is aging

Cheese cultures continue to transform lactose into lactic acid

The cheese will lose moisture

Both of these intensify the flavor of the cheese and also change the texture which we can just see with our eyes.

And based on the aging amount it actually can change the recommendation for a recipe we happen to be using it in.

For example, on the official Parmigiano website they have a filter for the aging time of the cheese that you have in order to find a recipe that best utilizes the characteristics.

And in general, the younger-aged cheese will be the mildest in flavor, have a higher moisture percentage, and have a lower melting temperature when compared to the longer-aged parmesan cheeses.

2. Pasteurized vs. Raw Milk

In general, the US is very conservative when it comes to food safety, so for mass-produced dairy products US dairy farms typically are going to pasteurize milk by heating it to a specific temperature for a set amount of time, and this process kills off harmful bacteria that could potentially cause disease.

But all bacteria are not bad and this process also kills off all of the bacteria that are responsible for developing flavor in the aging and lactic acid fermentation process.

In Italy, on the other hand, it is mandated that “Parmigiano Reggiano is a hard cheese made from raw cows milk” — meaning the milk cannot be pasteurized beforehand. The small, highly regulated Italian operations can keep a close eye on the cheese to make sure any harmful bacteria don’t show up in the end product.

Now if you ever tasted raw milk, they taste way different, but it’s hard to say exactly how much of a difference it makes in the final cheese product.

3. Additives

Parmigiano Reggiano, by definition and law, can only contain those three ingredients we talked about: milk, salt, and rennet, which is the natural cheese culture that coagulates the cheese.

US cheese companies on the other hand might mix in preservatives or enzymes to ensure their product is safe for mass production, passes FDA regulation, and has a long enough shelf life to be profitable at the grocery store.

Now on a US-made parmesan label there are 4 additional ingredients you could see:

Cellulose or Starch (anti-caking agents)

Potassium Sorbate

Natamycin

Enzymes

These are all food-grade additives that are passed by USDA, but do they significantly change the taste or texture of the cheeses?

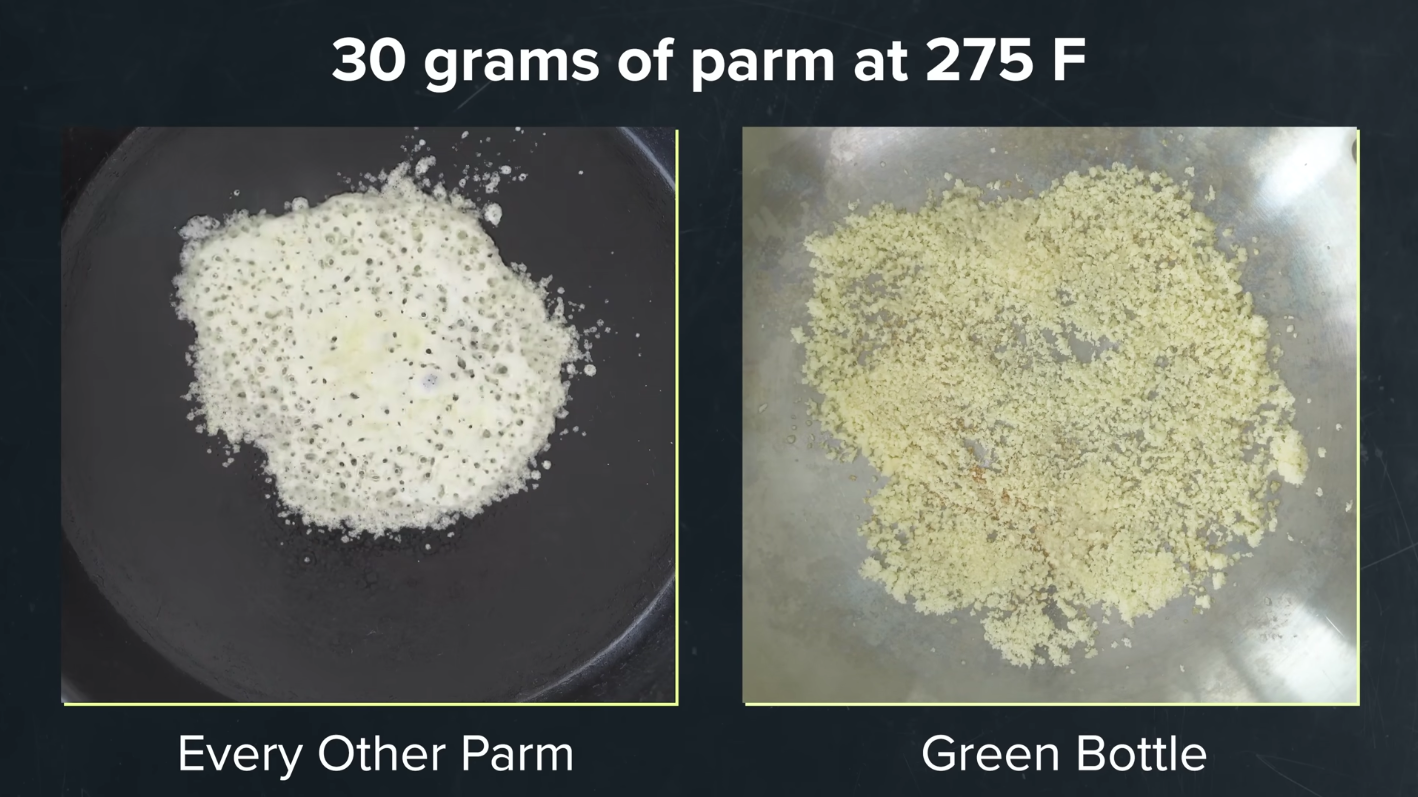

Well for one, when I added 30 grams of each of the grated parmesans to a 275 F pan, every single one of them melted except the green bottle, it kind of just browned, which is kind of weird.

What is causing this to not melt?

Well I think it has to do with a variety of general factors

Lack of moisture

Lack of fat

Tight protein structure of the cheese before being grated.

Which might partially be caused with

Added cellulose powder

Added potassium sorbate

So let’s talk about these.

Cellulose powder is a common anti-caking agent that is typically added to grated, shredded or shaved parmesans to keep them from clumping up. This alone won’t stop it from melting because the other pre-grated parmesan has cellulose as well but it melted just fine when I added 30 grams of grated parmesan to a 275 F degree pan, but I do suspect this is what caused the green bottle and the pre-grated parmesan to linger on my tongue in the raw taste test because cellulose is insoluble in water.

Potassium Sorbate & Natamycin are both common food additives that prevent the growth of molds and yeast, that will extend the shelf life, and protect flavor.

And then lastly, we have Enzymes, which I’m still not entirely sure what they are. I couldn’t find a direct answer, but Most US-made parmesans will list both cheese cultures & enzymes.

I assume the cheese cultures is referring to the rennet that is used to make cheese, but enzyme also seems to be a generic term when describing rennet too. So maybe there are additional enzymes that are not rennet that are added to the pasteurize the milk used to make the cheese.

In general, after reading into these, a lot of articles or videos may tell you to steer clear of the cellulose powder or anticaking agents if you want a smooth creamy sauce, but as I discovered in the Alfredo test, while not perfectly smooth, it still can be done.

We’ll get to that test in a moment, but lastly, let me talk about the final major difference between US & Italian-made parmesan.

4. Geography, Cow’s Diet, & Cheese Processing.

This last category is kind of a catch-all group for a lot of things that may make a difference in the texture and taste of parmesan.

It’s hard to objectively quantify exactly how much of a difference these factors make.

For example, the geography and land of the Reggio Emilia region play a role in the cow's diet since 75% of the dry matter they eat must be from the region.

Silage, a fermented preserved grass, common in the US is completely banned in Italian Parm:

Then lastly, they’ve been making Parmigiano in Italy for over a thousand years at this point so if there is anyone who has the process dialed down and regulated to ensure the best possible product in the world, it’s going to be them.

It’s fair to point out, that the US domestic products are probably worse for the consumer since there is less regulation around processing and labeling which leads to more confusion. They can boast flavor characteristics on the front, add marketing terms, be sold in any form factor, and use any of those additives we just talked about.

Can hundreds of years of Italian craftsmanship surpass modern dairy production methods? Will we really be able to taste any of these factors in the end product, especially in a cooked dish?

Enter the traditional Alfredo test.

Taste Test #2 - Traditional Alfredo

For this test, I did the traditional three-ingredient fettucine al burro. I made the cheese sauce with 25 grams of butter, 60 grams of each parmesan product, and starchy pasta water.

To make each, I added the butter over medium heat along with the pasta water and emulisfied them together, once mixed, I turned down the heat to low, and very important you need to keep the temperature below 160 Fahrenheit or else that cheese will seize up and get stringy as soon as you add it.

The younger-aged parmesans have a slightly lower melting point due to having more moisture and a looser protein structure, so I actually had to turn it down to 150 F to be on the safe side.

I’ve outlined the science behind all of this in my cacio e pepe video. The cheese-melting knowledge I discovered there is the only way I was able to successfully make a cheese sauce with each parmesan product.

Once the sauces were made, I mixed them with freshly cooked hot pasta to sauce them together. I blindfolded myself then did a taste test.

Alfredo Taste Test Results

Here is what I concluded about the sauce capabilities of different parmesans.

Can I make a sauce with all 5?

Yes.

But are there differences in how they distribute throughout the sauce?

And this is also a yes. The green bottle is noticeably grainy since it doesn’t really melt, and the younger aged versions have a slightly lower melting point so they are more prone to melting together resulting in a stringy sauce only if your liquid is too hot. Again, that goes back to technique (not the product) because I can make a stringy sauce with Parmigiano Reggiano if I wanted to.

Is there a noticeable flavor difference in the sauces?

Surprisingly, not really.

It was super hard to tell the differences between them once the cheese was dispersed among the butter, pasta water, and pasta itself. The only clear marker I said was that the 2 grated options tasted stronger. And I didn’t articulate it well in the taste test, but I didn’t say they tasted better or more flavorful so what I meant by that is they tasted saltier which makes sense on the nutrition label as the green bottle has double the amount of sodium per each 10 gram serving.

If it was hard to tell the difference, does this mean should I stop buying Parmigiano Reggiano?

I mean if you make a sauce with 2 parts cheese and 1 part butter of any kind, it’s probably going to taste good, but I think the main reason why I had a tough time differentiating the two is that I didn’t add any extra grated parmesan as a garnish.

And I did do this on purpose because I want to really isolate just the sauce in a cooked application because adding the garnish may have influenced me into thinking the sauce itself was more different than it actually was.

So, test number 3 is a garnish test.

Taste Test #3 Garnish on Pasta & Pizza

Then lastly, I did two garnish tests for both pasta and pizza.

Unlike in the pasta test, here I adjusted the amounts to balance out the sodium levels.

I made one mother batch by adding some sauce to a pan, tossing in a little cream and then adding cooked penne so those could get to know each other before portioning them out into 5 dishes. Next, I added the parmesan in varying amounts.

Then just because I was curious, I did one last garnish test with a slice of pizza.

I bought a massive slice, cut it into roughly equal size shapes, and then added each of the 5 parmesans.

The results? Nothing too surprising. The official Parmigiano Reggiano stood out as the best garnish, but to be fair — the 20-month aged US parmesan was also quite good.

The others were passable, but not as interesting as a garnish.

Final Conclusions: How to Shop for Parmesan

So in conclusion, is Parmigiano Reggiano actually worth it?

After running through these tests, I will continue to pretty much exclusively buy Parmigiano Reggiano for all of my parmesan needs.

However, I now have an appreciation and understanding for the other parmesan products in the US.

Let me give you some real-life examples of where it may make sense to use these:

For one, I’m not going to just throw the green bottle away. I’ll keep it in my fridge as a safeguard since it has a ridiculously long shelf life and use it sparingly for things like throwing it on popcorn, a slice of pizza, or just adding to a one-pot pasta that’s lacking salt.

Now, what about the middle-of-the-pack parmesans?

Say you are making alfredo or a carbonara for a family of 6 or a maybe bunch of friends of friends are coming over.

You are going to need a lot of parmesan in this case. So instead of dropping your entire budget on all DOP Parmigiano Reggiano, I recommend getting a cheaper US made, even the 12 or 16 month to make the base of the sauce, and then buy a small piece of DOP that can be used grated over top as a raw garnish.

I would wager that no one is going to be able to call you out on it. (“Are you trying to hide the fact that you used US parmesan in this alfredo sauce?”)

All considered, here are some general tips to keep in mind while buying parmesan:

If it’s labeled Parmigiano Reggiano, it's the real deal from Italy (most commonly 24-month is what makes it to US markets).

If it’s labeled Parmesan, it’s likely from the US.

Purchase a whole wedge or block as this will give you the most variety and control over the form factor.

For example, I would not recommend ever buying the shreds or the shavings if you are making a cheese sauce as they will increase the likely hood of the cheese getting stringy because they don’t disperse well in the sauce compared to a finely grated version.

Look on the label to see how long it has been aged.

Choose something aged at least 20 months for the best flavor, especially when used in raw garnishes.

If you want to see my live reactions, check out the full parmesan video here.

Sources

Official Parmigiano Reggiano Website: https://www.parmigianoreggiano.com/

Parmigiano Reggiano EU Specifications PDF: https://www.parmigianoreggiano.com/static/3bb2ed0dbce70d6851a111b1a8bd43ab/1d0c8e670c96c56f898e93203342681d.pdf

EU/Berlin Parmesan Lawsuit: https://www.dw.com/en/eu-commission-sues-berlin-in-parmesan-cheese-row/a-1262620

FDA Parmesan Regulations: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=133.165

On Food & Cooking by Harold McGee (Book) https://www.amazon.com/Food-Cooking-Science-Lore-Kitchen/dp/0684800012

Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking by Marcella Hazan (Book) https://www.amazon.com/Essentials-Classic-Italian-Cooking-Marcella/dp/039458404X